Bolivian Cholitas: Never Going Down Without A Fight

“I think that every woman has inside, I don’t know how to say it, a strength... a great strength that we don’t know how to get out”- Martha la Alteña.

The indigenous Aymara women of Bolivia can easily be spotted walking the streets of La Paz, and neighbouring El Alto, in their traditional, and eye-catching, style of dress. They are the ‘Cholitas’: strong women, now known internationally for their resilience, their fashion, and even their wrestling!

The term ‘Cholita’ was once a derogatory way of differentiating “them” from “us”. Associated with poverty, resigned to purely domestic roles, and ‘refused entry to certain restaurants, taxis and even some public buses’, the native Cholitas were marginalised for decades. But a 2013 shift in municipal law recognised the worth of this subculture. [1] This shift came as a result of the pride and determination of the empowered women who refused to let their heritage die. Like their grandmothers and mothers before them, modern-day cholitas don their costumes to announce to the world: “it is a thing of pride to be a Chola”. (Julia la Paceña)

Known first and foremost for their fashion, Cholitas proudly wear enormous skirts and contrastingly tiny hats. Amusingly enough, the bowler hats synonymous with Cholita style are said to have originated as a mistake: just like misreading the dimensions when placing an online order, these hats were shipped to Bolivia by westerners who had overestimated just how small these indigenous folk would be. As such, when the hats were all made too small for male heads, they were rebranded as female fashion. Still too small, they have to be worn perched atop one’s head, insisting on impeccable posture to keep them from toppling. For such a level of balance alone, these women are worthy of praise! Beyond that, by manipulating the fashion remnants of European colonial rule into a unique and local style, the hats act as a pre-Facebook announcement of relationship status: straight hat = married, wonky hat = single. (Sadly these precariously balanced accessories are removed before entering the wrestling ring.)

The rest of the outfit is a little more self-explanatory: long skirts, with layers upon layers of petticoats, enhance the illusion of a sought-after curvaceous figure, whilst the colourful shawls showcase style, vibrancy and personality with their infinite pattern possibilities. Finally, Cholitas unanimously wear their hair in two long, dark plaits.

Beyond all of this fashionable sticking-it-to-the-man, a select few of these women have chosen to marry the old with the new, to prove that Cholitas are capable of more than just housework and that image isn’t everything; week in, week out, these women enter the wrestling ring.

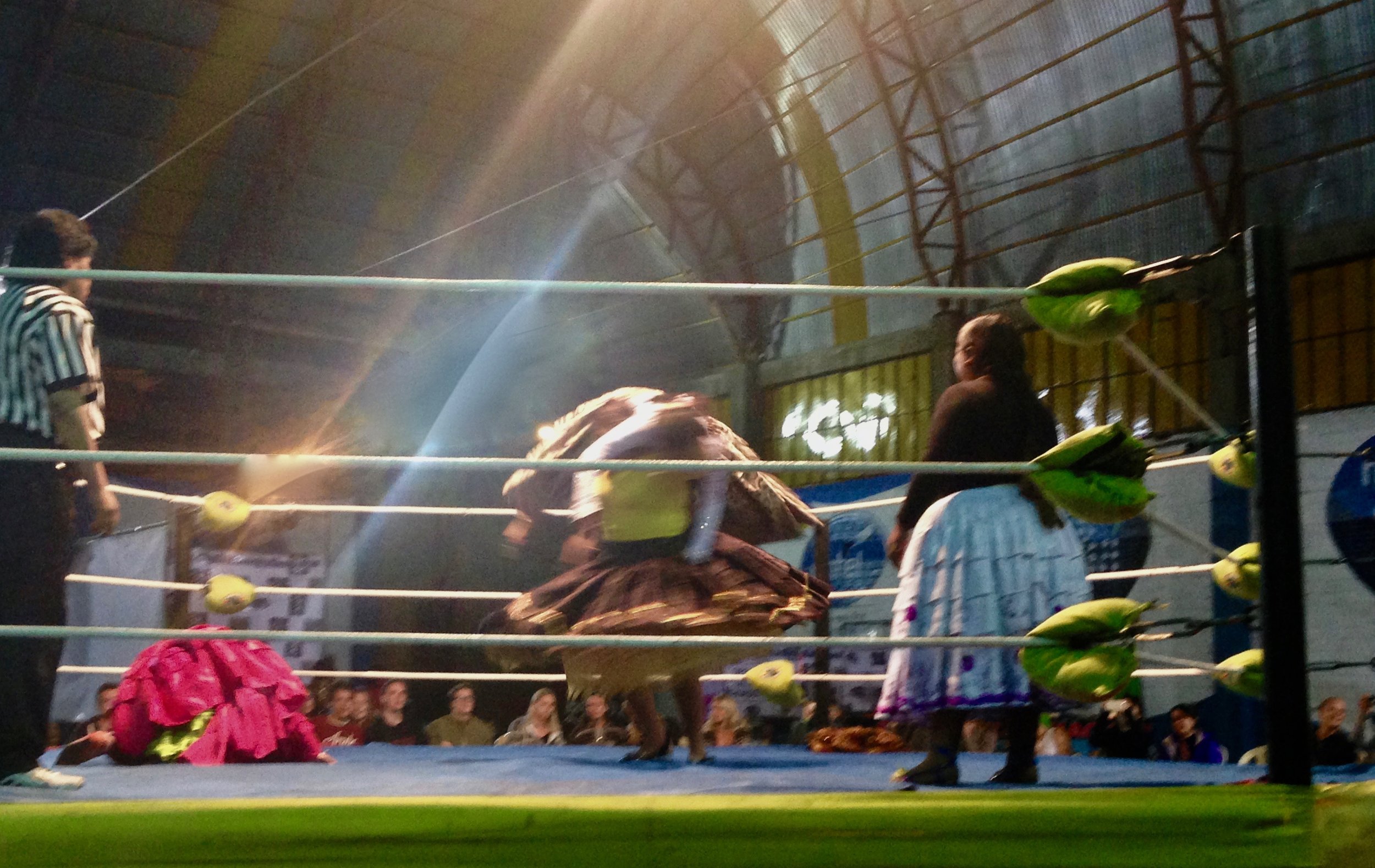

I didn’t know what to expect as I boarded a bus through the hectic, gridlocked streets of El Alto, en route to what appeared to be an old school gymnasium. We encircled the ring, sipping the drinks that came included in our ticket price, as we watched a group of flamboyantly dressed, masked men mount each other in a pantomimic fashion. So this was wrestling?!

But, just as I felt things couldn’t get any more surreal, the main event began: The Fighting Cholitas. Dressed exactly as one would expect from such traditionalists, the women paraded around, swishing their skirts, dancing and working the crowd. There was a clear performative split between who we were supposed to see as the ‘goodies’ and the ‘baddies’. I was mesmerised; these women were seriously strong! At once wincing with concern, as these small, buxom women hurled each other across the ring, I was also laughing hysterically at the bizarreness of the situation and the sheer performativity of some of the moves. Whether for the novelty of character wrestling or the draw of women rebelling from their allotted roles, these wrestlers had drawn a crowd and the crowd were enthralled.

The 2006 documentary short by Mariam Jobrani, ‘The Fighting Cholitas’, gives some of the fighters a chance to voice how wrestling makes them feel. Unanimously that feeling seems to be one of empowerment. Wrestlers Martha la Alteña and Yolanda la Amorosa both attest to feeling that the ring transforms them, from “ordinary” to “a little star”, from a single mother, to a “wild animal”. Yet this change happens only within, for, as Julia la Paceña claims: “we can’t take off our skirts to wrestle, we have to fight as we are, as Cholitas. I am fighting with my identity and it’s a thing of pride for me to take Cholitas higher, representing all the women that wear layered skirts, like my grandmother and mother.

It seems that what I was sold as a trivial tourist event means so much more. This literal fight represents the fight against the marginalisation of women and of their heritage. These women are strong, driven, and still manage to maintain a sense of humour around the melodramatic performative style. These women, amongst many others like them, have stood their ground against generations of down-treading, until Cholita fashion has become celebrated. They have proven their physical strength and resilience, alongside their ability to break the mould, to challenge expectations, and, what’s more, to do it all in a fabulous flowing skirt.

(Quotes from this article are taken from 'The Fighting Cholitas' film: https://vimeo.com/100569187)